What is a Writs and Appeals Attorney?

As it applies to me, a writs and appeals attorney is an attorney who practices in the area of civil writ matters, which involve litigating petitions for writ of ordinary or administrative mandate, prohibition or review in the superior court (the trial court); and litigates appeals, petitions for writ of mandate, prohibition, review, or supersedeas in the California and Federal Courts of Appeal and Supreme Courts. There is a somewhat coordinate practice in criminal law (i.e., a petition for writ of habeas corpus is the most well known), but I do not practice criminal law.

Confused?

Okay, I don’t get it – what’s a writ?

Good question. Writs go way back; they were issued in the name the English monarch and today in California, depending on what kind of writ you manage to get, they are typically issued by the court in the name of the People of the State of California and command the person upon whom they are directed to perform or refrain from performing a particular act. It’s sort of like a snooty injunction, and in almost all circumstances it is directed at a government body or agency, including trial courts. If you’re a public employee, you may seek a writ to compel your public employer to set aside discipline or take some other action.

Don’t give up yet – it gets more interesting:

Typically, there are two types of writ proceedings you may encounter, especially if you’re a public employee: administrative writs of mandate, and ordinary writs of mandate. There are also writ proceedings in the Court of Appeal, but I will discuss those in another post.

Writs of Administrative Mandate

This is sometimes known as a 1094.5 writ because it is a petition proceeding brought pursuant to California Code of Civil Procedure (CCP) §1094.5. Let’s say you’re a public employee (and you probably are if you’re reading here), and you’ve been disciplined: you were suspended without pay, or demoted, or even terminated from employment following an investigation. If you’ve already completed the probationary period and are a permanent employee, federal due process usually entitles you to a pre-disciplinary hearing (called a Skelly hearing in California). If after the Skelly your employer still disciplines you, due process entitles you to an administrative appeal.

At that administrative appeal, your employer will have the burden to prove the charges of misconduct against you, and that the discipline is warranted by those charges if proved. These hearings are usually conducted by a lone hearing officer (or arbitrator), or some type of commission or board that hears employee disciplinary matters. You’ll usually have an attorney who specializes in administrative hearings represent you. Witnesses are called by both sides, there are a lot of objections and yelling, and usually accusations that a witness is lying or sleeping with a supervisor. Eventually you get a decision from the hearing officer or commission. This may be the final decision, or a board, city council, or city manager may make the final decision (in which case you may lose even if the hearing officer thought you should’ve won).

Let’s say you lose, and the discipline is upheld. You are entitled to have a superior court review the administrative proceedings and final decision. To get the ball rolling, you file a Petition for Writ of Administrative Mandate. It’s sort of like a complaint in a lawsuit, but because writs are special proceedings, you file a petition instead.

Procedurally, this type of writ proceeding is somewhat like an appellate matter. There is no jury, and there is no live testimony. All of the evidence in an administrative mandate proceeding is confined to the administrative record: the transcripts of the testimony at the administrative hearing, all exhibits, notices and the final decision. Instead of testimony from witnesses, the parties file briefs citing to the testimony, exhibits, and other evidence. Then the parties appear before the judge and argue the case. If you’re the petitioner, you have to argue why the decision of the public agency is wrong: you might argue the factual findings are against the weight of the evidence, or that the discipline is too excessive, or both.

Shouldn’t I just use the attorney who handled my administrative hearing? They are already familiar with the evidence and know my story.

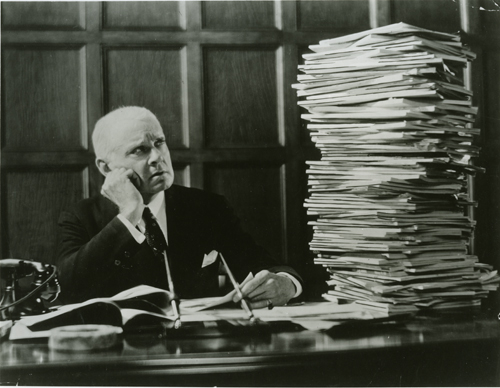

You could, but conventional wisdom recommends against it. Unlike at the administrative hearing, this time you have the burden and the court is required to presume the disciplinary decision is correct; you have to prove why it’s wrong. Because of the limited scope of review the trial court employs—in other words, it’s not a redo of the administrative hearing, it is not enough to merely point out conflicting witness testimony or make the same arguments your attorney made at the administrative hearing. And because the judge has not viewed the witnesses and observed their demeanor, he or she will often (though not always) defer to the hearing officer’s credibility determinations. All the judge has before him or her are the cold words on a transcript for a case he or she knows nothing about.

This is why you should seek an attorney who specializes in writ proceedings. The rules are completely different from the rules at the administrative hearing, which are usually relaxed and informal. It is imperative that the attorney understands the differing standards of review employed by the court when looking at your disciplinary case, and how that affects the arguments you can make and how to present them. Arguments that fly before a hearing officer might not be appropriate before a judge in a writ proceeding, and the attorney has to use the standard of review to his or her advantage. In fact, it is often legal arguments, and not evidence arguments, that lead to success in a writ proceeding.

I believe there is another distinct advantage to using an attorney other than the attorney who handled your administrative hearing, and it has nothing to do with specialized skill: to be sure, the administrative attorney is completely familiar with your case, and lived it as well through the many days of hearing; indeed they are also very qualified to handle such proceedings. Yet, they are naturally entrenched in and attached to the arguments they made at the administrative hearing and are less likely to shift gears away from those arguments when doing so would be appropriate or helpful for the writ proceeding.

When I first take on an administrative writ of mandate case, I am in the same position as the judge: I know nothing about the case; and like the judge I have no opinion about it. Just like the judge reading your case, I have only a cold transcript and exhibits before me. I have to approach the case in the same way the judge does: I have to work my way through the case, and spot not only the strengths but also the weaknesses because the opposing party is going to point them out and the judge is going to see them. I have to formulate the arguments from scratch and get there myself, and they may be very different from the arguments made at the administrative level.

about the case; and like the judge I have no opinion about it. Just like the judge reading your case, I have only a cold transcript and exhibits before me. I have to approach the case in the same way the judge does: I have to work my way through the case, and spot not only the strengths but also the weaknesses because the opposing party is going to point them out and the judge is going to see them. I have to formulate the arguments from scratch and get there myself, and they may be very different from the arguments made at the administrative level.

And if I can convince myself of certain arguments based only on my review of the cold and often dry administrative record, then I stand a better chance of convincing a judge those arguments are correct because we’re both starting from the same place: a huge stack of paper sitting on our desks that we know nothing about.

I will write about the other types of writs and appeals in the near future. Come back and check out this site as it develops.

Thanks!